This post on hazard and risk is part of a collaboration between neuroscientist Alison Bernstein and biologist Iida Ruishalme. Errors in risk perception are at the core of so many issues in science communication that we think this is a critical topic to explore in detail. This series is cross-posted on SciMoms and Thoughtscapism.

The difference between hazard and risk is a critical distinction

Hazard and risk describe two different but related concepts. The difference may sound like an unimportant jargon-filled distinction, but this difference is critical to understanding reports of hazards and risks.

- A hazard is an agent that has the potential to cause harm.

- Risk measures the likelihood of harm from a hazard.

Hazards only become risks when there is exposure. Sharks are a hazard. But if I never go near the ocean, I have no exposure to sharks and face no risk of a shark attack. (Granted, even if you go in the ocean, the risk of shark attack is actually very low.) Despite this difference, we tend to consider all hazards as risks, regardless of our level of exposure.

The video from Risk Bites (also embedded at the bottom of this article) explains this distinction very well.

Hazard classifications are not risk assessments

One area where this confusion between hazard and risk is very visible is in the classification of carcinogens. Hazard identification is the first step of risk assessment, but is not in and of itself a risk assessment. However, we consistently see reports of hazard identification presented as evidence of actual risk.

These problems are particularly prominent in connection to the reports by the International Agency on Cancer Research (IARC). IARC has come under fire by scientists for not being clear about its communication of hazard vs risk. In a 2016 paper (Classification schemes for carcinogenicity based on hazard-identification have become outmoded and serve neither science nor society), toxicologists explicitly criticize such classifications and call for more modern approaches based on both hazard and risk characterization instead.

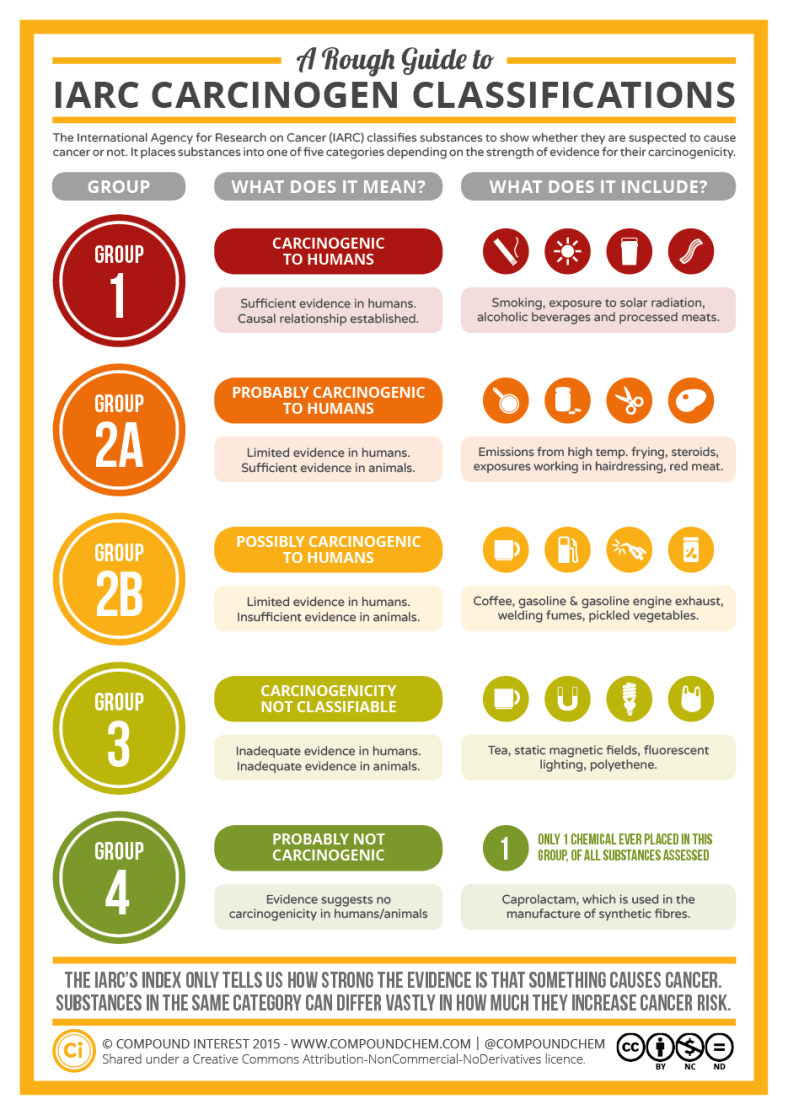

If we look at the IARC classifications in detail, it becomes apparent why relying only on information about hazards is problematic. As Ed Yong wrote in 2015 in The Atlantic in “Beefing With the World Health Organization’s Cancer Warnings”,

These classifications are based on strength of evidence not degree of risk.

Two risk factors could be slotted in the same category if one tripled the risk of cancer and the other increased it by a small fraction. They could also be classified similarly even if one causes many more types of cancers than the other, if it affects a greater swath of the population, and if it actually causes more cancers.

So these classifications are not meant to convey how dangerous something is, just how certain we are that something is dangerous.

But they’re presented with language that completely obfuscates that distinction.

This is a critical distinction. Strength of evidence reflects how certain we are of the potential to cause harm (in this case to cause cancer). Degree of risk reflects how much a compound increases risk, the number of people it increases risk in, or the numbers of cases of cancers caused by that compound. It is also important to note that risk is a probability of harm and does not reflect the severity of harm; it merely represents that change of that harm occurring. The IARC categories are a confusing measure of the quality of the data, not a measure of how risky exposure to that chemical is.

This graphic by Compound Chemistry and the accompanying post shows which exposures fall into these categories.

Smoking and eating meat

Here’s an example that highlights the confusing nature of these classifications: smoking and eating meat are in the same category (Group 1). However, as noted on Compound Chemistr

According to Cancer Research UK, smoking causes 19% of all cancers; by contrast only 3% of all cancers are thought to be caused by processed meat and red meat combined. To put this in a little more perspective, it’s estimated that 34,000 cancer deaths worldwide every year are caused by diets high in processed meat, compared to 1 million deaths per year due to smoking.

While we have strong evidence that both can cause cancer, these clearly pose different amounts of risk. Confused yet? Not surprising. As Ed Yong writes in the article mentioned above, these classifications are “confusogenic” to humans.

When we, as parents and consumers, see these classifications, understanding the difference between hazard and risk can help us to keep risks and dangers in perspective.

If you would like to read more about different aspects of risk perception, please see the other parts of the series, which this article belongs to:

- The difference between hazard and risk is a critical distinction.

- All hazards are not equal.

- Zero risk and zero exposure are impossible expectations.

- Population risk is not the same as individual risk.

You must be logged in to post a comment.