This post on zero risk and reducing risk is part of a series written as a collaboration between neuroscientist Alison Bernstein and biologist Iida Ruishalme. Errors in risk perception are at the core of so many issues in science communication that we think this is a critical topic to explore in detail. This series is cross-posted on SciMoms and Thoughtscapism.

Alison and Iida would like to thank Anne Martin for her graphic design work in translating our abstract ideas into graphics. Anne is a designer, illustrator, and researcher currently finishing her PhD in Neurobiology and Anatomy at the University of Utah. You can see her work through her website at hungrybraindesign.com and follow her on Twitter @thehungrybrain. She also runs a blog teaching researchers how to visually communicate their science at vizsi.com.

We often strive for choices with zero risk. However, zero risk is an impossible goal. Certain activists and consumers seem to want an even more conservative goal of zero exposure, whether there is risk or not. Zero risk and zero exposure are impossible goals. Nearly everything we do has both risks and benefits. Everything, even inaction, carries risk. Thus, decisions, both personal and regulatory, are a matter of balancing the relative risks and benefits of your choices and choosing the level of risk you find acceptable, rather than of trying (and inevitably failing) to avoid all risk and all exposure to hazards.

Removing risks and exposures does not always reduce total risk

This phenomenon is readily apparent in our widespread outrage over trace amounts of chemicals. We tend to assume that the mere presence of tiny amounts of a substance is as risky as any other hazard, even without evidence (or even a plausible mechanism) for harm. Some activists and consumers demand the removal of these trace amounts without consideration of the risk of removal or the replacements. There are real-world consequences to this misguided activism.

- BPA is replaced by very similar chemicals, so-called “regrettable substitutions”, allowing companies to slap on a BPA-free label with no actual benefit to consumers.

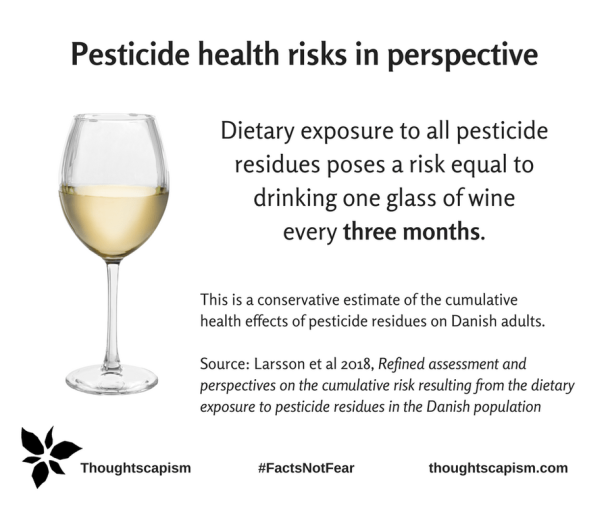

- People who cannot afford the premium for organic produce avoid fruits and vegetables out of fear of pesticide residues, even though the risk from exposure to dietary residues is extremely small for both organic and non-organic produce and the risk from not eating enough fruits and vegetables is larger. Fear of trace amounts of glyphosate, in particular, leads to use of more toxic and environmentally unfriendly herbicides.

- Inflated sense of dread toward radiation and nuclear power results in increased reliance on coal power, which not only spreads more radioactivity into the environment in the form of coal ash, but produces particulate air pollution that costs several million lives per year the world over.

- The false idea that “natural” medicine is less risky leads people to choose natural remedies for cancer over conventional cancer treatments. Those who choose alternative therapies are more likely to die than those who choose conventional cancer treatments.

- Historically, consumers in the US have tolerated the use of flame retardants in furniture and textiles. However, the safety benefits of these measures are so slight that many scientists believe that lack of benefit does not justify exposing the whole population to the health risks (even if they are small) of exposure to these chemicals.

Exaggerating the risk of the unfamiliar

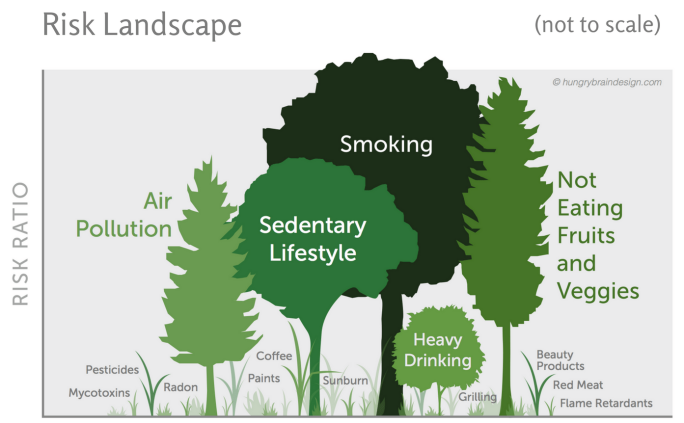

One of our fundamental cognitive biases is that we have an outsized focus on novel and unfamiliar risks. Novel risks are inflated in our thoughts, not due to their impact, but merely because of their newness or our lack of personal control over them. Contrast this with well-known, big-impact risk factors, such as a sedentary lifestyle, eating too few fruits and vegetables, smoking or drinking alcohol, and excessive sun exposure. Despite the large influence of these factors on many aspects of health, we don’t feel the same sense of alarm and urgency about these high-risk, yet familiar risks.

Stress about risks poses a health risk

We have a tendency to underestimate the effect of chronic stress on our health. While dangerous exposures overall have greatly diminished in the developed world, the knowledge of these hazards has become a source of anxiety, partly due to a broader scientific understanding of risks and exposures. In many cases, this chronic stress is a larger risk factor for disease than the exposures we are worried about. According the American Psychological Association, who conducts an annual “Stress in America” Survey:

“While people can overcome minor episodes of stress by tapping into their body’s natural defenses to adapt to changing situations, excessive chronic stress, which is constant and persists over an extended period of time, can be psychologically and physically debilitating.

Unlike everyday stressors, which can be managed with healthy stress management behaviors, untreated chronic stress can result in serious health conditions including anxiety, insomnia, muscle pain, high blood pressure and a weakened immune system. Research shows that stress can contribute to the development of major illnesses, such as heart disease, depression and obesity. Some studies have even suggested that unhealthy chronic stress management, such as overeating “comfort” foods, has contributed to the growing obesity epidemic.”

While some may dismiss worry about exposures as a cause of chronic stress, a few minutes in almost any parenting forum online will show that many consumers feel that they are living in a constant state of danger from the world around them. (Note: this is not to say that there are no real risks and dangers in modern, developed communities. However, the degree of fear about many hazards and risks is highly exaggerated.)

The risk landscape

It is important to remember that in many areas of human health, we have already identified the big risk factors. These large risk factors are the old and familiar ones, like excessive smoking and drinking, or skipping daily fruits and vegetables. In addition to the big factors, research is now able to identify smaller and smaller risk. We are down in the weeds teasing apart the things that contribute to the background levels of risk in the total population, or that pose risks to specific vulnerable populations.

Medicine and public health measures, based on these large risk factors, have enabled people in developed countries to attain a generally high level of welfare. Thus, we have become increasingly aware of smaller and smaller risks. This is not necessarily a bad thing as health and safety are more important to us than ever before — as long as we take an evidence-based approach to risk and managing risk.

If you would like to read more about different aspects of risk perception, please see the other parts of the series, which this article belongs to:

Risk In Perspective: Introduction

- The difference between hazard and risk is a critical distinction.

- All hazards are not equal.

- Zero risk and zero exposure are impossible expectations.

- Population risk is not the same as individual risk.

You must be logged in to post a comment.