March was Brain Injury Awareness Month, which aims to raise awareness about traumatic brain injury (TBI) and to help make life better for those with TBI and their families. We often hear about head injuries, concussions, TBI, and chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE) in professional athletes who play football and other contact sports. As a result, some parents are concerned about kids’ concussions and head injuries when playing these contact sports. While half of kids’ concussions and head injuries occur from other activities like bike riding, skiing, skateboarding, trampolining, or sledding (like Alison’s 8-year-old this winter), this post will focus on head injuries from sports, and how to prevent them.

What are common types of head injuries in kids’ sports?

There are many specific terms for types of head injuries that we often use interchangeably. However, to understand the risks associated with head injuries, it’s important to know the differences.

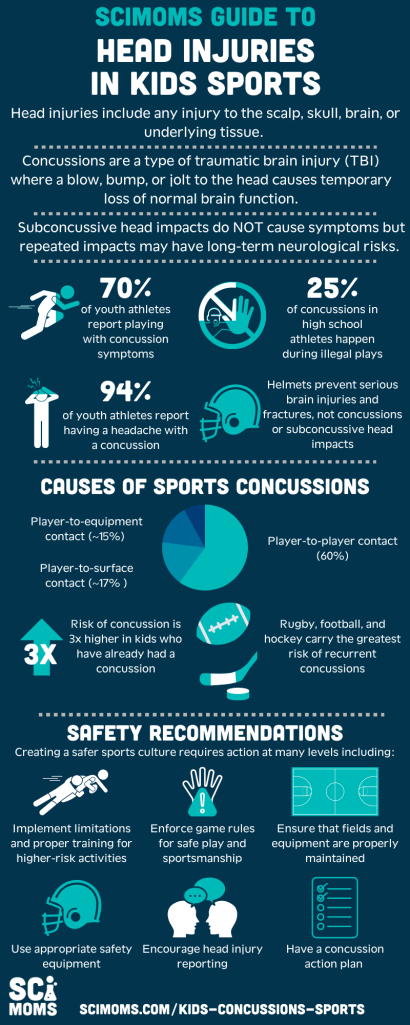

According to Johns Hopkins Medicine, head injuries include any injury to the scalp, skull, brain, and underlying tissue, including bumps, bruises, and cuts, that can range in severity from mild to life-threatening. In youth sports, head injuries come with potential for concussions, or a type of traumatic brain injury (TBI) in which a blow, bump, or jolt to the head causes temporary loss of normal brain function.

But concussions aren’t the only concern. As scientists learn more about head injuries in kids, doctors and parents have become increasingly concerned about the long-term risks of repeated subconcussive head impacts, which are impacts to the brain that do not produce immediate symptoms and do not lead to concussions. Repeated injuries of this type can increase the risk for Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy (CTE), a progressive and fatal neurodegenerative disease.

Which sports cause the most concussions and head injuries for kids?

In kids, the main risks for head injuries from sports and physical activity are related to concussions and subconcussive head impacts. While head impacts can occur in many activities that our kids participate in, contact sports present a higher risk because impacts to the head occur more frequently. The most common cause of concussion in sports is player-to-player contact (over 60% of sports-related concussions). Player to surface and player to equipment contact are each responsible for about 15% of sports-related concussions.

Sports where these types of contacts are more common come with a higher risk of concussion. At the high school and college levels, American football, ice hockey, lacrosse, wrestling, and soccer have the highest reported concussion rate in people who played on men’s teams (in decreasing order). In those playing in women’s leagues, ice hockey, soccer, lacrosse, basketball, and field hockey have the highest rates (in decreasing order). Baseball, softball, and volleyball have lower concussion rates. Non-contact sports like swimming, track and field, and cross country have the lowest incidence of concussion.

In addition, recurrent concussions, which are a major concern when it comes to head injuries, are most common in rugby, ice hockey, and American football. In any sport, kids who have previously had a concussion are at more than 3 times higher risk of having another concussion.

The available statistics provide an incomplete snapshot of sports-related head injuries in kids, so there still isn’t sufficient data to provide a clear understanding of the risks involved in specific activities, especially for subconcussive head impacts. The Traumatic Brain Injury Program Reauthorization Act of 2018 updated how the CDC monitors head injuries and TBIs in the population. This law directed CDC to launch the National Concussion Surveillance System to improve how we count concussions and TBI and to determine the cause of these injuries. One specific goal of this program is to generate the first national estimates of youth sports-related concussions both in and outside of organized sports. This data will help scientists learn more about the risk factors for long-term problems from head injuries and inform better prevention and mitigation strategies.

What are the symptoms of kids’ concussions and head injuries?

The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) recommends watching for the following signs and symptoms of concussion after a head injury, starting immediately after the injury occurs. It is important to monitor symptoms for a few days, as some do not appear immediately after the injury.

- Appearing dazed or stunned

- Forgetting instructions, positions, or being unsure of activities being performed

- Clumsy movements, slow responses, sluggishness or grogginess

- Loss of consciousness (even briefly)

- Change in personality, mood, or behavior, or simply feeling different

- Inability to recall events before or after the blow, confusion, or difficulty concentrating

- Headache, nausea, dizziness, or loss of balance

- Sensitivity to light or sound

- Change in sleep patterns

Subconcussive head impacts by definition do not produce symptoms of concussion.

How long will my child need to recover from a head injury?

Each concussion is unique — the time and the extent to which the child needs to rest will depend on the symptoms of each concussion. However, most children will recover from a concussion within 4 weeks. The brain is particularly vulnerable to injury while it heals, so it’s best not to rush to resume normal activities.

Returning to school and physical activities should be a gradual process. The CDC recommends following six steps towards a return to school, physical activities, and eventually competitive sports. Details about when to proceed to the next step are available on CDC’s HEADS UP website to guide parents, healthcare providers, coaches, and schools. CDC has also developed an app to help monitor kids for concussion symptoms after a head impact.

The AAP stresses that a child doesn’t need to be 100% recovered or symptom-free before returning to school. Instead, a child can return to school “[w]hen concussion symptoms have lessened and are tolerable for up to 30 to 45 minutes,” which should happen within a week of the injury. However, returning to school does not mean returning to normal activities, particularly athletics.

The AAP also highlights that while a child is recovering, even after they’ve returned to school, all physical activities should be canceled (this includes recess, PE classes, dance classes, and all school or club sports). Recovery in the classroom is crucial before returning to sports and physical activities. Teachers should allow for a reduction in academic demand during the recovery period.

The CDC also provides guidance for schools and sports programs to implement policies to guide the safe return to sports following an injury. The AAP also recommends a set of 10 questions to determine when an athlete is ready to return to play after a concussion. While we highlight key points of this guidance, it is critical to review this guidance with doctors and coaches if your child has a concussion.

You may have heard that you need to wake kids up throughout the night, but AAP guidance says that’s not necessary. Sleep is an important part of recovery and there’s no need to interrupt it. While experts recommend a break from sports and a reduction in activity, they do not recommend complete bed rest. Finally, you do not need to eliminate screen time during recovery — electronics can be an important way to stay connected and reduce feelings of isolation.

What are the long-term risks of kids’ concussions and head injuries?

There is a potential for long-term neurological risks, including behavioral and cognitive problems and CTE, from repetitive head injuries, even subconcussive head impacts. However, there is a lot we don’t know about the long-term risks of multiple concussions or subconcussive head impacts.

The earliest research on CTE and its causes largely focused on adult professional athletes, especially football players and boxers. But newer research on youth, high school, and college athletes suggests that these risks are also present for kids, even if they never play professional sports.

Data from youth tackle football show that playing tackle football before the age of 12 is associated with increased neuropsychiatric, behavioral, and cognitive problems later in life. Importantly, this association was not related to the number of concussions a player suffered. This suggests that repeated subconcussive head impacts at a young age might have profound long-term effects. Research in this area is still very new so we don’t yet know specifically how these long-term risks relate to the frequency of head injuries, the severity of head injuries, or the age at which the injuries occur. However, it is becoming clear that the earlier head injuries occur and the more frequent they are, the greater the potential risk of long-term effects. Overall, we need increased monitoring of head injuries in kids and more research to understand the long-term impacts.

What can we do to reduce the risk of head injuries in contact sports?

Although there is a lot we don’t know about the long-term impact of head injuries, especially repeated head injuries, we know enough to say that we should take measures to lower the risk of head injury and subconcussive head impacts and to ensure that children recover well from concussions. As we learn more, recommendations will likely change.

Schools and leagues that your kids participate in should have concussion and head injury policies in line with CDC and AAP recommendations. These include the use of required appropriate safety equipment, like helmets, adopting and enforcing return-to-play guidelines, and implementing limitations and proper training for higher-risk activities like tackling in youth American football and headers in youth soccer. CDC provides guidance for coaches, parents, officials, and youth athletes about these policies. (See CDC’s HEADS UP Initiative for full details, especially this page with recommendations for concussion prevention for sports in general and for activity-specific recommendations).

Reporting head injuries to coaches and parents are also critical. However, many children do not report head injuries. Kids worry that their parents or coaches view injuries as a sign of weakness, about letting their team down, losing their position on the team, or jeopardizing career plans. There are resources to help parents and coaches talk to kids about the importance of reporting when they have hit their heads. (See CDC’s Opportunities to Reshape the Culture Around Concussion).

The only way to completely avoid sports-related head injuries is to avoid sports (especially contact sports), but for many people, this is not a reasonable option. Sports are fun, part of our culture, help build community, and can be an important source of physical activity. Fortunately, there are several factors within our control to help kids participate as safely as possible in these sports. CDC, AAP, and other experts have issued recommendations discussed here to help educators, parents, and coaches minimize the risk of head injury and mitigate harm from them.

Resources

Concussions: What Parents Need to Know – HealthyChildren.org

Sports-Related Concussion: Understanding the Risks, Signs & Symptoms – HealthyChildren.org

After a Concussion: When to Return to School – HealthyChildren.org

When is an Athlete Ready to Return to Play? – HealthyChildren.org

Opportunities to Reshape the Culture Around Concussion

A Fact Sheet For Youth Sports Coaches

Head & Brain Conditions — Recognize to Recover

Frequently Asked Questions about CTE | CTE Center

This post was co-written by Layla Katiraee and Alison Bernstein.

You must be logged in to post a comment.